Comparative habitat use of ringed and bearded seals

Overview

This is a cooperative project between Native Village Kotzebue (NVOK) and biologists to compare the seasonal movements, habitat use and foraging behavior of bearded seals (bottom feeders, prefer pack ice) and ringed seals (water column feeders, prefer fast ice) in the Chukchi and Bering seas by satellite tagging 12 individuals of each species in fall 2009. This project builds on two previous projects funded by the US Department of the Interior Tribal Wildlife Grants (TWG) program: “Community-based tagging of bearded seals” from 2004-2006 and “Wintering areas and habitat use of ringed seals in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska: a community-based study” during 2007-present.

Our most recent TWG project proposed to conduct two years of field work (2007 and 2008) and put satellite tags on 20 ringed seals. Because of our early success in 2007 (16 tags the first year), we looked for and found funding to purchase additional tags for 2008. Shell provided the funds to purchase 13 tags. We deployed 13 tags in 2008, but still had 7 tags left. We decided to try for one last year of fall tagging. Kathy Frost and Alex Whiting wrote a proposal to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) to conduct a comparative study of the movements and diving behavior of young ringed seals and bearded seals in the same year. The proposal was successful and NVOK received the funds to purchase 15 tags to be placed on bearded seals in 2009. This new component supplements the TWG project to tag ringed seals.

Information on seasonal movements, habitat use and dive behavior are very limited for ringed and bearded seals in Alaska, despite their importance for subsistence, as a major prey of polar bears, and as species likely to be greatly impacted by climate warming. Satellite tagging conducted by this project will begin to provide such information and will serve as a baseline for evaluating future environmental change.

This project has involved local participants in all aspects of the project. Local participants catch, tag, measure, weigh, draw blood and sample seals. Two local participants are authorized under ADF&G’s research permit to conduct these activities. Project results will be presented at meetings and workshops by both local participants and biologists. Kotzebue High School students have or will be involved in several ways. Students observed seal tagging and sampling activities on three occasions in 2009. During the school year, project participants (biologists and local) will speak to students about the project and its findings. Location data from tags will be provided to teachers for mapping exercises by students throughout the school year (as long as tags are transmitting). It is also the goal of the project to invite new ice seal researchers in Alaska to participate in the project and learn about the advantages of cooperative projects involving both biologists and local participants.

Objectives

- Acquire baseline data about habitat use and foraging of bearded and ringed seals to guide human development activities (oil & gas development, mining, shipping, fishing) in seal habitat, Endangered Species Act decisions and to evaluate effects of climate change.

- Improve ice seal co-management by strengthening partnerships between ice seal subsistence users, Tribal governments and state and federal agencies.

- Increase stewardship of ice seals by involving hunters in the collection of data that will be used in management decisions.

Activities

- Satellite tag 12 each ringed and bearded seals in fall 2009 to learn about habitat use and foraging behavior. Map movements of tagged seals by season, sex and age and relative to ice cover and water depth.

- Distribute maps to industry, agencies and others for use in management plans, permits, designation of critical habitat and other

- Analyze dive data to detect feeding behavior and areas, depths or regions important for feeding and make this information available to decision makers.

- Archive all tag data at the National Marine Mammal Laboratory or the Alaska Department of Fish and Game so it is available for future comparisons and decision making.

- Report movements and dive behavior in a user-friendly format on the Kotzebue IRA website and in a newsletter-type community report to Kotzebue Sound residents.

- Make maps available to polar bear biologists for use in evaluating polar bear prey availability and changes that may occur with climate warming.

Importance of Bearded and Ringed Seals

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MPA) requires that marine mammals be managed to ensure that they retain their function in the ecosystem, and that species harvested for subsistence by Alaska Natives be managed to ensure a sustainable harvest. These goals were established in recognition of the importance of ice seals to the functioning of the arctic marine ecosystem and to the human cultures that are part of that ecosystem.

Bearded and ringed seals are important for four main reasons:

- They are important subsistence resources. Bearded and ringed seals are harvested for subsistence by Alaska Natives throughout northern and western Alaska , with an estimated annual harvest of about 10,000 ringed seals and 7,000 bearded seals. Bearded seals are the most important marine mammal subsistence species for hunters in Kotzebue Sound and they are harvested extensively in spring on the pack ice and fall in open water and as freeze-up approaches.

- They are likely to be indicators of, and greatly affected by, climate change in the Arctic . Bearded and ringed seals depend on sea ice for hauling out and as substrate for rearing their pups. Their sea ice habitat will likely be affected by climactic warming trends and diminishing sea ice cover in the Alaskan Arctic. Existing information indicates that ringed seal densities in the Kotzebue Sound region are among the highest in Alaska, and in some years are 10 times higher than average densities in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas. In the future, the extensive land fast ice of Kotzebue Sound may provide particularly important pupping habitat as sea ice break up becomes earlier in coastal regions of northern Alaska.

- They are the major prey of polar bears. In 2008, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed polar bears as threatened under the Endangered Species Act because their populations are likely to decline as a result of warming climate. Ringed seals are the primary prey of polar bears and the welfare of polar bears is dependent on the welfare of ringed seals. Information about seal habitat use and response to changing sea ice conditions will be important in understanding effects of climate change on population trends of polar bears. In the past, declines in ringed seal numbers and productivity have resulted in marked declines in polar bear populations. Future fluctuations in ringed seal abundance and productivity caused by warming temperatures will likely impact polar bear reproduction and cub survival and affect the status of this at-risk species.

- They occur in areas where human activities occur and are likely to occur more extensively in the future. A variety of industrial activities occur in the Chukchi Sea and near Kotzebue Sound in areas where ringed seals are found, for example the Red Dog Mine and proposed Port Site expansion north of Kotzebue. The Minerals Management Service has announced a 2007-2012 oil and gas leasing plan that includes the Chukchi Sea . Both mining and oil and gas activities will likely result in increased shipping traffic and other human activities in ringed seal habitat. Port Site expansion may alter local sea ice conditions, thereby affecting seal habitat. Information provided by satellite tags will help to identify important seal habitat and aid in the development of guidelines to minimize impacts of human activities on these seals.

Benefits of Ringed Seal and Bearded Seal Tagging Research

Collection of data from both bearded and ringed seals during the same year increases their usefulness for understanding differences in habitat use and diving behavior. Often when comparisons are made, data from multiple years and ages classes must be combined to provide an adequate sample size. This study will allow direct comparison of species with quite different feeding modes and habitat preferences. Bearded seals are found mainly in pack ice in winter and are known to feed primarily on benthic invertebrates. In contrast ringed seals prefer stable shore fast ice and feed on fish and plankton. It is not known, however, whether young seals show these same strong differences. Survival is lower for young seals than for adults and may be more readily affected by climate-caused changes in prey type and abundance or environmental conditions. Young-of-the-year seals are learning to feed independently and body size may limit diving behavior. This study will provide information on these vulnerable and poorly known age classes.

Understanding bearded and ringed seal ecology in the Chukchi Sea is critical given the rapidly changing ice environment and other expected developments including increased industrial exploration, shipping and potential commercial fishery expansion into the Arctic Ocean and its adjacent waters. In September 2008, the National Marine Fisheries Service announced that it would initiate a status review to determine whether bearded, ringed and spotted seals should be listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act ( ESA ). Despite these pressing concerns, information on seasonal movements, habitat use and dive behavior is very limited for bearded and ringed seals in Alaska . Satellite tagging conducted by this proposed project will contribute such information. We will document seasonal movements, identify important foraging habitat, and assess individual and species differences in habitat use and foraging behavior. Data will serve as a baseline for evaluating future environmental change. This information will help with the development of guidelines to assess and minimize the effects of human activities. There is a need for quality ecological data to inform decisions and implement real mitigation measures if and when human activities increase in important seal habitat.

This project involves Tribal members in planning and conducting research activities, and will serve as an example for how this can be done in other areas. In the past, many marine mammal research projects in Alaska have been conducted with little or no involvement of local Tribal members in planning, field work or interpretation of results. This project is ground-breaking because Tribal members are responsible for developing capture techniques and tagging seals. Two Tribal participants are included as Co-Investigators under the scientific permit to conduct this work. This project is one of the few times in Alaska that Tribal members have been trained and authorized as Co-investigators under a marine mammal research permit.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act states that the government may enter into cooperative agreements with Alaska Native organizations to conserve marine mammals and provide co-management of subsistence use by Alaska Natives, and that the agreements may include grants to collect and analyze data on marine mammal populations, monitor their harvest, participate in research, and develop co-management structures with federal and state agencies. This proposed project directly addresses these MMPA provisions for Alaska Native involvement in marine mammal research and management. This project will also bring new, young agency biologists into the field and expose them to this collaborative mode of research. Both ADF&G and NMFS have new marine mammal program biologists who are new to Alaska and new to working with Alaska Native subsistence hunters. They will have a chance to see the effectiveness of local participants, the benefits of locally-based projects, and to learn about subsistence lifestyles. This will promote understanding between researchers and local people. This sort of collaboration and exposure leads to the inclusion of local participants in other research projects, either on research cruises to study ice seals or as teachers and mentors when other similar collaborative projects are established in other areas.

By involving Kotzebue High School students in this project, we hope to develop enthusiasm for learning about ice seals and understanding marine mammal conservation and management issues. These students are the future of marine mammal management in their communities and it is important for them to have experience working with their elders, as well as biologists and agency personnel, in a collaborative research environment.

Methods

Tribal members were involved in all stages of the study, including planning, tagging and biological sampling. Tribal members have received training in the handling, measuring, sampling and tagging of seals in previous years or as part of this year’s study. Two Tribal participant “taggers” were designated as Co-Investigators under the marine mammal research permit under which this project operates, and they were authorized to tag and sample seals. Additional Tribal members participated in, learned about and were trained in catching, tagging and sampling seals.

The goal for the 2009 field season was to tag 12 ringed seals and 12 bearded seals. The Principal Investigators were Kathy Frost, Alex Whiting , and John Goodwin . The Research Assistants were Brenda Goodwin, Pearl Goodwin, Cyrus Harris, Levi Harris, and James Monroe. Seals were tagged under Alaska Department of Fish and Game Scientific Permit No. 358-1787-02.

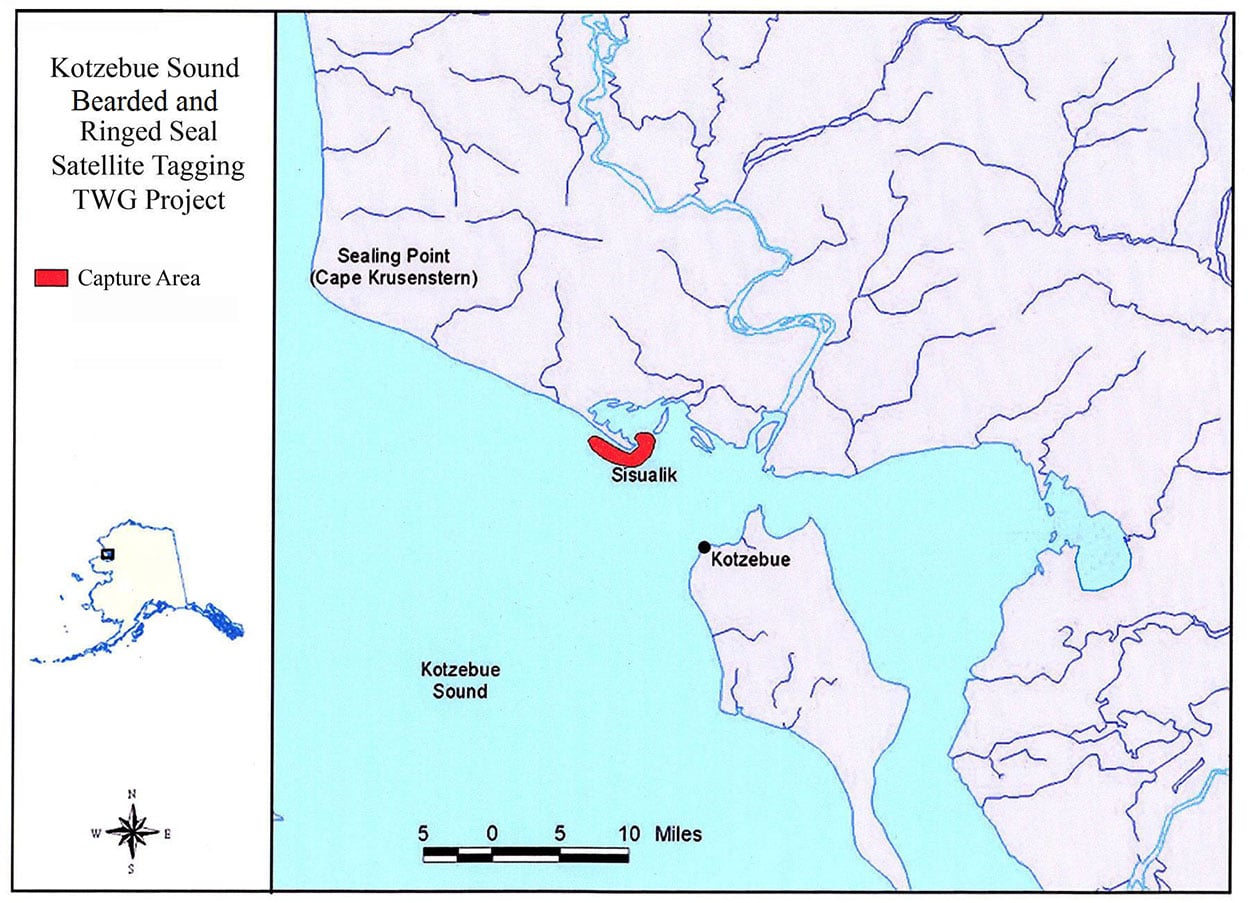

The base of field operations was located at the Tribal Elders Camp at the tip of the Sisualik spit 10 miles north of Kotzebue across the inner Sound. John Goodwin was the field manager of the camp and directed catching and tagging activity. There were two 3-person seal catching crews, one led by John Goodwin and the other by Cyrus Harris.

The field camp was operational from September 25 th until October 13th. Biologist Kathy Frost arrived in Kotzebue on October 1st and left on October 14th. North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife biologist Jason Herreman who will be conducting ice seal studies for the NSB flew to Kotzebue on October 7 th and spent several days at seal camp learning about the tagging operation. Other biologists were unable to visit because they were preparing for and attending the biennial marine mammal conference in Quebec.

Northwestern Aviation supplied transportation to and from Kotzebue for personnel and supplies. All-terrain vehicles were used to transport supplies, gear, seals, personnel, boats and generally be able to move about Sisualik. Boats small enough to be beached were used to check nets.

Both bearded and ringed seals were caught using standard “seal nets.” The nets were constructed of 10-in to 12-in stretch mesh and had light lead lines and foam-core float lines. Each of the two crews had its own boat and set out and tended two 250-ft seal nets. Some nets were modified to have a monofilament net “hook” set at 90 degrees to one end of the net. When a seal tried to swim around the end of the standard heavier-meshed net it got caught in the less visible monofilament. The nets were set at different locations along Sisualik spit, Nuvuguraq and Egg Island depending on water and ice conditions and where the seals seemed to be. Monofilament nets were used only during daylight hours and only when they could be closely monitored. Kotzebue Tribal members conducted all seal capture activities.

The first young bearded seal (ugurachaq) was caught on September 20 th . Because one of our goals in 2009 was to involve Kotzebue High School students, the 188 pound animal was taken to Kotzebue and tagged where the students and teacher could watch and ask questions. A second 210 pound bearded seal was caught on September 21 st and this seal was also tagged in Kotzebue where students could observe. This was a great opportunity for students to observe the research activities and to see trained and experienced local participants conducting all aspects of tagging and sampling.

Other seals were processed and tagged at Camp at Sisualiq. When a seal was caught, it was removed from the net and placed in a hoop net in the boat for transfer back to the beach. Seals were taken out of the boat and moved from the boat to camp using an ATV with a trailer to hold the seal.

When a seal reached camp, it was either sampled and released if it was too small or tagged if it was big enough. The seals that were released without satellite tags were weighed and measured. Sex was recorded, a small skin sample was taken from the hind flipper for genetic testing, blood was taken, and a numbered plastic tag was put in the hind flipper. Measurements included curve length from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail, straight length from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail, girth behind the front flippers, and maximum girth around the belly.

Blubber biopsies were taken from some seals. These samples will be analyzed for their fatty acids. The fatty acid signature analysis provides information about what the seal was eating in the month or so before it was caught. This is because the fatty acids in the prey they eat are transferred into the seal’s blubber without being changed. It is possible to match the fatty acids in different fish and invertebrates to the fatty acids in blubber and know what the seal was eating.

All bearded seals and any ringed seal larger than 50 pounds were also satellite tagged. The taggers rubbed the fur dry. The tags were fitted in the neck saddle as it slopes towards the shoulders. Tags were placed slightly farther back on bearded seals because of they way they swim and roll. The correct spot for the tag was drawn with a black marker. The 5-minute epoxy glue was mixed in two small batches. The first batch went onto the bottom of the tag and also on the mesh (if used) and fur of the seal. The glue was spread in a very thin layer so that it didn’t get too hot on the seal’s skin. When that layer dried, the second batch was used to cover any places that were missed. After the second layer of glue was dry, the tag was turned on, data sheets were checked to make sure the tag number was written down and all of the data were complete, and the seal was taken to the water and released.

We hope to involve Kotzebue High School students during the school year through class discussions of the research project with both biologists and local participants, and class participation in data mapping and analysis exercises.

Location

The area of investigation is in northwest Alaska , specifically northern Kotzebue Sound. The field camp is located at Sisualik Spit about 10 miles north of Kotzebue.